Rating 6/10

The magic of creation

Unusual combinations are not new to movies, but when it was announced that one of America’s most adult auteurs of the past generation would make a film for children, eyebrows were raised. Martin Scorsese directing a kids’ movie? Will Quentin Tarentino be doing an episode of Teletubbies next? Are we to see Al Pacino pull a gun on Peppa Pig? Now there’s a thought.

Instead of falling prey to the potential laziness which kids’ movies seem to bring to otherwise level-headed directors, Scorcese allows the built-in wonder of youth to infuse what is otherwise one big love letter to movies themselves.

Instead of falling prey to the potential laziness which kids’ movies seem to bring to otherwise level-headed directors, Scorcese allows the built-in wonder of youth to infuse what is otherwise one big love letter to movies themselves.

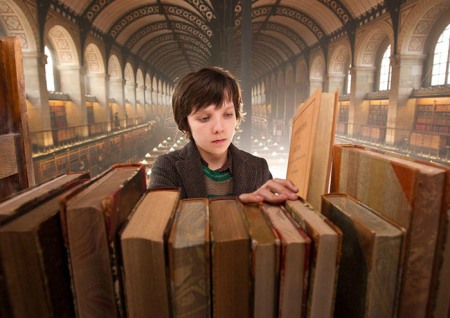

Hugo revolves around a young boy who lives in the walls of the Montparnasse station in Paris. Alone, his only connection to his past is a clockwork automaton which refuses to start operating.

He passes his time by maintaining all the station clocks, while stealing parts from the station’s toy shop, hoping they can make the metal figure work. The shop’s owner, a wise but sad Ben Kingsley, catches him in the act one day, setting in motion a series of events which, much like the spinning cogs and wheels which constantly surround Hugo, change people’s lives.

Yes, there are typical kids’ movie elements. Hugo’s constant nemesis is a Clouseau-esque policeman played with pantomime glee by Sasha Baron Cohen (of Ali G, Borat and Bruno fame) who spends most of the time trying to catch him. Certainly for the first half of the film there are enough of these moments to satisfy the younger members of the audience.

But then you come to realise it’s still a Scorsese story. The second half is as introspective and melancholy as one of his classic films. There is an insight into broken dreams and failed ambitions which kids simply won’t grasp. This is the reason adults will stay to watch.

What stops Scorsese from going full adult, so to speak, is his determination to re-capture our child-like wonder at the magic of cinema. He deliberately chose 3D because of its wow-factor. It most closely re-creates that sense of awe which led the first audiences to see ‘moving pictures’ to flee the cinema from a short clip of oncoming train. That early history of cinema is also the bedrock upon which Scorsese builds a second half aimed at anyone who care about movies.

The clockwork figure at the heart of Hugo’s life is a symbol of the brokenness which he, as well as other characters, experience. It is clear something is missing, that it lacks what Hugo calls a purpose. And everyone, he believes, is only ever truly happy when they fulfil their purpose. In the case of the automaton, there is a literal hole which needs filling before its purpose can be realised.

For those like us who believe in the creator God, this is a recognisable concept. To be created is to be made for a reason – even if that reason, at its most fundamental, is simply to love other people. We understand the need which exists in the soul – the God-shaped hole which atheists mock so readily. And we know how it should be met, whether feeding the homeless, campaigning for justice or evangelising to a friend. We’re never more alive than when we fulfil our purpose.

Scorsese knows this. But he also makes it clear that a machine is still just a machine, however well it works. The magic comes from the act of creation.

Hugo is a rare thing – a movie for parents and kids alike. The kids will come for the dog-chases, pratfalls and 3D. The parents will stay for Ben Kingsley and for cinephile Martin Scorsese’s ode to the men and women, and their dreams, of the early history of film.

Pingback: Anna Karenina | Here Be Critics